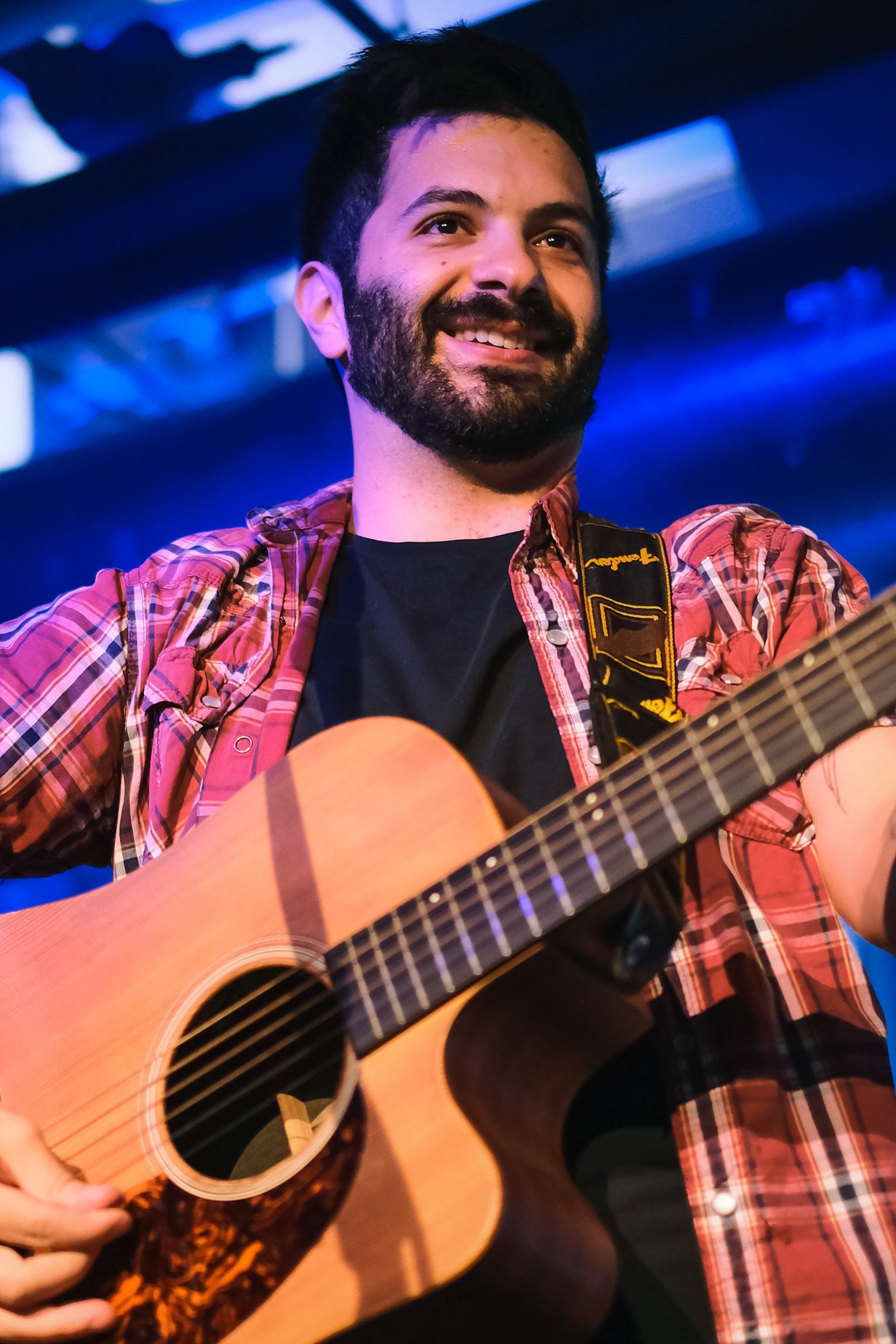

Behind Closed Doors with Alex Petti

Alex Petti is a Lebanese Irish-Catholic writer from Massachusetts who grew up as a pop punk rocker. He is a 2023 Artist in Residence at Keepsake House and will be performing in our upcoming show, Outside the Lines. Tickets are on sale now! In this interview, Alex chats with Hailey and Autumn about what Wicked has in common with Warped Tour, how to break down Arab stereotypes, and his commitment to community building.

In this blog series, we post in-depth interviews that take you behind closed doors (or #BCD) with independent artists, many of whom have performed or will perform in a Keepsake show. You can also watch the full interview on Youtube!

Hailey:

I'm going to hit you with a really hard one first, it's gonna get really intense… How are you celebrating St. Patrick's Day?

Alex:

I am going to celebrate St. Patrick's Day like a good Irish Catholic boy, probably by drinking a green beer by accident.

Actually, I’ll revise my answer. Ready? I'm celebrating St. Patrick's Day by avoiding Midtown on St. Patrick's Day. The number of times I've accidentally ended up there, y'all. It's a problem.

Hailey:

Now an actual question. You grew up in Massachusetts. Can you share a bit about your background, how you discovered theater, writing, or both, and any events or memories that drew you there?

Alex:

I grew up in Massachusetts and I feel really distinctly shaped by where I grew up, in the family that I grew up in. I was raised Catholic, my mom's side of the family is Lebanese and Irish Catholic, and I was sent to Catholic school for K through 12th grade, and I think it really shapes who I am as a writer and an artist. There's this really vibrant Boston punk scene that I grew up aspiring to be a part of. And also, I went to school with a lot of Irish Catholics and folks that maybe didn't look exactly like me. And as a Lebanese person, I always kind of felt like a little bit of an outsider at school, maybe because of my interests, maybe a little bit because of the way that I look too. But I found writing to be a really good escape from that kind of stuff. It was a way to express myself and start to cope with things, and with mental health issues that were on their way, but not fully onset yet.

“There was this kinship between theater kids and punk kids, we were all “island of misfit toys” kinds of folks”

I didn't discover theater until college actually. I just played in a band in high school, and then when I went to college, I didn't have a lot of friends in high school, so I was [looking for] ways in which I could make friends. And I knew something about sound engineering and sound design from my work in my band. [I thought I should] cast as wide a net as possible, you know, this is my second chance, really can't blow it. I did my first college show as part of the sound tech crew for a production of Urinetown with Scotch'n'Soda. And I just fell in love with the environment. There was this kinship between theater kids and punk kids, we were all "island of misfit toys" kinds of folks. And as time progressed through college, my interest in theater grew and grew until I decided that I wanted to take my composition in that direction, and use some of the singer/songwriter stuff that I had learned to apply to theater pieces, and really use writing and music to advance my political stances through theatrical messaging.

Autumn:

That's really interesting. I didn't know that there was that kind of kinship between theater kids and punk kids. Can you talk a little bit more about that, the relationship between those two styles of music? Because they seem very disparate.

Alex:

Totally. I think it's more like the type of person that's attracted to those genres. I do think there's a connection between theater and punk, or at least I'm trying to make one. But there's this thing with theater kids where they have these really niche interests but they're all secretly like, “But I just love Legally Blonde: The Musical.” And also, theater doesn't make sense. It's a crazy thing to be like, yeah, we're all gonna stay up all night building this set, painting this set, in addition to our schoolwork, because we love it so much.

So there's this misfit toys thing happening there, where you don't all fit together with the main group, but you all have this thing in common that you love. And I always found the punk spots were the places for the weirdos and the kids that didn't fit in. A lot of my friends in school and I sometimes had imposter syndrome, like I was cosplaying as a punk, but that's what I aspired to be, right? Those were the people who [expressed] the things that were weird about them, or aggressive, or these political stances, and I loved bands like The Matches that were doing something different.

They were dressing in wacky clothing, and they were painting their nails, and they had crazy hairstyles and all this stuff. And the whole punk "I Don't Give a Fuck" thing was something that really appealed to me, because it's not just I don't give a fuck in a vacuum, right? It's like, I don't give a fuck what you think about me. I like the way I look with my painted nails, or I like the way I look with my hair spiked or whatever, and I don't give a fuck that you don't like it. And there was something that was really empowering about that. None of the people in high school liked me––clearly I still have a chip in my shoulder about it––but with punk music it was like, fuck them, they're not cool, I'm cool. I do the thing that's cool now and straight up, [look at the scoreboard]. Now I'm a musician in New York and most of them are lame and live in the suburbs, so take that, people from Xaverian High School!

Autumn:

Honestly, that's so real. I grew up in Staten Island and I still live in Staten Island. For those who don't know, that's like the Ohio of New York City.

Alex:

That's such a tough hit. But that's fair.

Autumn:

Yeah, it's just very suburban, very conservative, just soccer moms everywhere, that kind of thing. And I have a similar story to you, where I started as the suburban kid, and then I went to high school in New York City. And I had this same kind of arc of being around people who were just very diverse and different. It made me realize I didn't have to fit myself to the people I saw around me growing up. I can actually express myself and be myself.

Alex:

Yeah, that's very resonant to me. I don't have to choose to fit in with this group, even though they're the dominant subgroup. Actually, I had a friend of mine say this to me once––when I was trying to break into theater circles that I couldn't get into––and they were like, Look, that validation, that [institutional] co-sign is great, but what's even cooler than breaking into someone else's circle is making your own circle.” Then other people [start to think] that's cool. I want to be a part of that! And I found that in theater and punk.

Autumn:

On that subject, something that you mentioned in your bio is that your dream when you were younger was that you wanted to headline Warped Tour. Can you talk a little bit more about what Warped Tour is, for people like me who don't know, and what it means to you, what it represented to you growing up?

Alex:

Warped Tour was… oh man, it used to be this super cool thing. It was basically this massive traveling festival that would play not just venues, but parking lots of venues. And the bills would have a hundred, two hundred bands on them. It was basically a traveling Coachella. And back in the day––I think Warped Tour doesn't exist anymore––but it existed for about 25 years or so, and back in the early 2000s it was the bill to be on. It was this summer tour, it came to all the venues all around the country, and it was the tour to be on for punk and pop punk and alternative bands. And all the punk classics, like Rancid and Brand New, all these bands were the headliners of Warped Tour and it was like a status symbol kind of thing. Like Blink-182 was name checking it in their songs, "couldn't wait for the summer in the Warped Tour," in that tune [“The Rock Show”].

“You heard it here first, hot take from Alex Petti: Wicked is good.”

So it was this cool status thing, and I've had that line in my bio for 10 years or something because it really holds up, right? Again, [Warped Tour] was partially a status thing, but it was also this place for these punk weirdo kids like me to go and just be free for a day, just like run around in a parking lot, push people to loud music, shout and sing along and stuff like that. And one of the reasons I really got into playing and writing music was that I wanted to be that conduit for people too. It was something that I found so freeing and so beautiful and I wanted to be a part of that.

I think my line in my bio is something like, "although my dreams of headlining Warped Tour have ended, the energy still infuses my music." And I think that's a really good descriptor of where I am. I'm really shaped by that era of music, in that pocket of music. And even if [there was a] Warped Tour Revival or whatever, I don't think I would want to do something like that. But the feeling, the vibes of it, are something that I really try to bring to my live shows.

Hailey:

We're going to segue back into Broadway, because like you said, there is some overlap in that punk and theater are two genres and communities that you deeply love.

What are your three favorite Broadway shows, currently running or not?

Alex:

Oh man. Okay. I'll just go with the things that jump to my head. I'm such a simp for Kimberly Akimbo, it's not even funny. Janine Tesori is the composer on it, and she is just this masterful writer who knows how to take something so small, like a small town story, and make it feel so big and life-encompassing.

Then I'll name check Hedwig and the Angry Inch. Talk about Broadway-punk crossover. I feel like such a fraud in theater spaces because I've discovered these shows more recently than I should have. But I saw it in I think 2015, when it was doing a revival run on Broadway, and that was hugely influential to me because I [realized] this is also theater. For those that don't know, Hedwig is a story told through a concert setting, where the concept of the story is that it is Hedwig's concert, and Hedwig is telling the story of how she got to where she is today through the diegetic songs in the concert. And it's so cool because the music is punk music. You can tell these songs weren't written on a piano. These songs rock and they rock hard, and part of Hedwig's appeal is that she isn't the best vocalist, but she really rips it and brings the house down. [Those are] the two things I love! This is music with storytelling and it's in a concert format.

And then my third one—it's such a basic answer, but I don't care—Wicked rips. Wicked is so good. I saw Wicked for the first time in 2022.

Hailey:

I haven't seen it!

Alex:

Yo, okay, Hailey, you and me, we're going. You name the time, the place, the day I'll be there. I love Wicked.

Before I went to see it for the first time, I was like, “yeah, Wicked will be good, of course. It's Wicked, right?” But it was one of those shows [that will be open forever so you put off going]. But finally, Omicron happened, the tickets were super cheap, so I saw it. And the whole time, like Act One, I'm [just] shocked at how good it is. It holds up. The songs are so good. Wicked. You heard it here first, hot take from Alex Petti: Wicked is good.

Hailey:

The musical you wrote, The Trouble with Dead Boyfriends, is headed for its off-Broadway debut, I heard. Congratulations! What has that journey been like for you? For those who don't know, you wrote the music and lyrics for this show. How can people see the show and support you and the cast and crew?

Alex:

We are at the Players Theatre from June 15th to July 16th. We play Thursday through Sunday, so we have 20 shows we're doing over five weeks this summer. We're really thrilled about it!

To really timestamp it, this show was started when Obama was still President. It's been around for a minute. We started it in September 2016 and the show's been just kicking around and being revised for a long time. But to give the quick pitch of it: it's the story of these three high school girls who are all trying to snag their perfect date to prom, with the one caveat that each of their boyfriends is dead and terrible in a different way. So you've got a vampire who's just obsessed with turning her, and that's all he cares about. [There’s] a ghost that's too possessive, you get the gist.

So The Trouble With Dead Boyfriends has been around for six, seven years, and the journey's been a really non-linear one. We were in talks to start doing some stuff in 2019 and then this crazy thing happened in 2020, and we kind of put it on hold for a couple years, and then we got this opportunity to do the self-producing residency at the Players Theatre, and we're really psyched. We're going to share this out with a broad audience, and this is my first off-Broadway show. And if folks wanna support us, the most important, best thing that you can do is buy a ticket and come hang out with us. We are a beautiful, 100-minute, beginning of your night, barrel-of-laughs kind of wild show to come and see, in an off-Broadway space in the West Village. So convenient. And then follow us on our socials. We're going to be posting updates as we start rehearsals and start to build this thing out.

Autumn:

Speaking of collaborative art as opposed to, you know, just being a soloist, you're also in a band called good thoughts. Can you tell us a little bit more about your band and how it started?

Alex:

I played in bands growing up in high school. And then I made this pivot to the theater career, which obviously I'm still sticking with. But in the pandemic it became incredibly apparent to me how much I missed playing live music, and playing my own live music, and how much fulfillment I got out of that. [So I] started to put together an EP of songs that we released in 2021 as good thoughts.

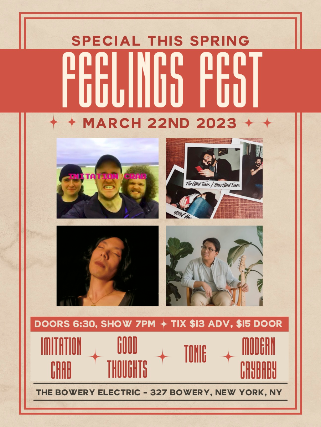

The drums on that record are played by the drummer from my high school band, Ken Bousquet, still playing in some bands up in Boston—K.C.U.F. and Coffin Salesman, if folks wanna check those bands out. Everything else on the record is me. I recorded guitars, bass vocals, mix and master, with a couple of guest additional vocal spots. And we've been playing as an outfit since then, since Fall 2021. We play as a five-piece around New York City and we've got our next show coming up on March 22nd at Bowery Electric. We'll be playing with fellow Keepsake artist TONIE. And over the course of the next year or so, good thoughts is going to be releasing three or four singles that will probably all add up to an EP.

Alex and TONIE will be performing in a shared show, Feelings Fest, at Bowery Electric on Wednesday, March 22. Tickets are available now!

Autumn:

So you've written music in a lot of different spaces—for theater, for bands—and I imagine you've written stuff that you can just play on your own as well. What is it like moving from the soloist perspective, where you're just worried about what you're doing, into collaborating with a band, and with a group of people for theater? Do you feel like you're like the head of the ship, and you make the decisions and then you pass that along to everyone else? Or is it a really collaborative process where everyone gets together and writes the song all in the same room at the same time?

Alex:

What a great question. Technically I'm the only official member of good thoughts, so for that I'm definitely like head of the ship, kind of in charge. And I don't want to frame this as a dictatorial thing, but I'll give people their charts for their parts and then we'll collaborate on making it all come together, making the sound feel right for everyone. Writing-wise, though, that's all generated from me, versus working with theater collaborators.

“What’s so wonderful about the collaborators I’ve been lucky enough to work with is they can catch a lot of my blind spots.”

[For theater,] I work with Annie Pulsifer, who I wrote The Trouble with Dead Boyfriends with. I've written with Claire-Frances Sullivan. Sometimes I collaborate and co-write some singer/songwriter stuff. I write with Sophia DeLeo a little bit, and have written with some other folks. And the vibe is very different for a collaborative thing. Part of the challenge of it is, whatever I say goes when I'm in those solo sessions, so I get to steer the song in whatever direction I feel is right, which has its pros and cons, right? It is nice to be able to [decide that a song will] be a hard rocking song, versus a collaborator who's going to force me to see some nuance. And what's so wonderful about the collaborators I've been lucky enough to work with is they can catch a lot of my blind spots. They can catch the things that I don't see. And if I'm a good student of what they're teaching me, I can learn a lot about stuff that I can apply to my own writing.

Autumn:

What's a blind spot you had that someone helped you catch?

Alex:

One of the most challenging things for me is I'm an over-writer, and I know I'm an over-writer. I like words, and I need to make sure that everybody knows exactly what I mean, with no confusion whatsoever. Sophia DeLeo is really good about pushing me on this. If I'm trying to state something and I'm trying to overstate it, we'll pause and [ask], “What is this verse going to be about? Or what is this song about? What is this chorus about?” And try to distill it into one line. Sophia is really good about catching me and stopping before I get too far into a lyric. She’ll ask me, “What is the lyric supposed to say? Okay, let's write it out and make it say that.” That's been really good for me. Working with collaborators has really helped me focus on simplifying the writing and trusting that the audience believes that what you're feeling is what you're feeling and it's going to get there.

Hailey:

I feel like your music toes the line between drama and comedy. You sang the Jeff Bezos song at Foresight, our last show that you were in. That song is hilarious and most of your songs have that element of comedy and energy, but they can also be really dark. [Your songs are] often story songs that are based in reality. "Sit Back" directly references [the 2020 Beirut explosion]. Does this dual personality feel like a conscious choice that you're thinking about when you write, or is it just a natural reflection of how you see the world?

Alex:

I think it's a little more latter than the former. I wouldn't say it's a conscious choice, with the one exception of when I wrote the Jeff Bezos song [when I decided that] I need to clown on this billionaire asshole, and billionaire assholes in general. With that one, [I wanted to write] a funny song. But I really don't think that I write a lot of haha-funny songs. I like to write stuff that's kind of just the way that I see the world. I've struggled with depression—I'm very open about this—and I've had suicidal ideations in the past. Some people are really serious about that, and for a long time I was really serious about it. I would be uncomfortable whenever someone brought the topic up. But for me, the fact of the matter is just that there's comedy in everything. There's stuff about depression that's so funny.

One of my bits that I use all the time is: the most infuriating part about having depression and being told to go on a little walk or exercise or drink water more, is that it works. It's infuriating! It's so frustrating. I gotta get up again, go outside and it's gonna help?! Ugh. Terrible. And that's the thing, I'm joking about a thing that did almost take my life. But at the same time, I feel like I have to be able to joke about stuff.

I write about the stuff that keeps me up at night. You referenced the song "Sit Back," and I wrote that song during the pandemic, the chorus of which is just, “I sit back and relax as the world is ending.” And like a lot of people, I wanted to write some pandemic art, but I wasn’t going to write [too] directly. I tried to consume as much news as possible [at the time], because that made me feel like I had control over it. And [I felt like] in reality, I'm doing nothing. I'm learning stuff to no ends, to no means. I wanted to write [about that feeling], you know? When my dad had appendicitis and almost died when I was 16 or so, [I was desperate for the update], to know what was going on. And all I [was] doing was just spinning my wheels, waiting to see if a doctor can do his job. So when there was this port explosion in Beirut, I did some fundraising and whatever, but what I was so frustrated about was that I felt such survivor guilt.

“I write music for people to be able to understand me, and without the sharper edge I don’t think people get the full picture.”

I don't have a lot of folks [I know left in Beirut], but I do have a community of folks that are Arab and Lebanese who had relatives stuck there, and you know, you can raise money, you can do the Instagram donation match stuff, but at a certain point there's not much you can do about it. So that song's not so haha-funny, as much as it's silly that I'm worrying about my forgotten gloves [in the lyrics]. All that to say, this is just the way I see the world. I write music for people to be able to understand me, and without the sharper edge I don't think people get the full picture.

Autumn:

Yeah, for sure. And it's kind of connected to your background in punk rock too, because punk and ska and everything, the whole idea of the art form is that it's giving a voice and levity to something that's really dark fundamentally. It's confronting all the struggles of life and all the insanities of the modern world, but it does it with blaring trumpets all the time, and really upbeat tempos, and it's cool to see how that same spirit manifests in your writing today as well.

Alex:

Yeah, yeah. There's a lot of that. A lot of pop punk stuff has that detached irony of songs in major keys that are upbeat and sound really happy, and are about people not doing well. And to me, that resonated with me so much as a kid, and even now, because that's how I feel all the time. I'm upbeat, I'm happy, I'm doing the thing, I'm good at socializing, but underneath the surface I'm still me. I'm still trying to figure out how to deal with that and feel better about it.

Watch the highlights from Foresight, including a clip of Alex performing the now infamous Jeff Bezos song. Footage by Justin Onne.

Autumn:

Yeah, totally.

You participated in the Johnny Mercer Foundation Songwriters Project last year, and it’s my understanding that you applied a few times before getting in. What was it like applying for the same thing over and over again? How much did it mean to you?

Alex:

This is one of the things I'm really proudest of as an artist. There are some folks who apply to things and get in on their first try, because they're just that good. And respect to them, no shade from my end, but that just hasn't been my journey. Some of the biggest things I've got in my career were getting into the BMI Lehman Engel Musical Theatre Workshop, which took me four tries to get in. I got into the Johnny Mercer Foundation Songwriters Project––which is an amazing program that I can't recommend enough––and it took me six tries to get in. It's really hard! One of the things I'm proudest of is my resilience as a writer. I know how to take it on the chin and [understand that] I applied and my songs were not good enough, or maybe it wasn't the year for me or whatever it is. Maybe the selection committee had their group and there was someone that was too [similar to] me and they [decided to go in] a different direction [...] But applying, continuing to apply, and just pushing myself as hard as I can to keep writing better and better songs is something that I take a lot of pride in.

I was not a savant growing up. I never was a savant when it came to songwriting or music theory or playing guitar. I was good, I'll admit that I was good, but to get to where I am today has been a lot of hard knocks and a lot of people telling me no, and me saying, “Okay, I will come back and I'll be better next time.” I'm really proud of how I've grown as a songwriter in the last six years or so, because I did get better. Getting rejected from that program forced me to get better, and eventually I got in and it was incredible. I met some of my best friends, friends that I'd never known before, going into that program.

The Johnny Mercer Foundation Songwriters Project is basically this weeklong songwriter's retreat that happens at Northwestern University. There are four masters teachers, or at least there were when I did it, a couple from the theater realm and a couple from the pop songwriting realm. You get selected, they fly you out––which is very cool, makes you feel very VIP––then you get put into a dorm room, which does not make you feel very VIP. Then you’re on Northwestern's campus for a week, and from day one [...] you have to write songs.

The cover art for “Everything About You,” the upcoming good thoughts single to be released on April 7, 2023, and which Alex wrote during his time at the Johnny Mercer Foundation Songwriters Project. Pre-save the song now!

But it was this incredible experience, me and 11 other songwriter or songwriter teams showed up in the same place, and we all presented one of our old songs, and then just wrote new material all week and kept presenting it out. And there was this beautiful game of one-upmanship happening, where nobody was trying to top each other, but everybody wrote incredible songs day one, and then came back with even better songs day two, and then better and then better. I wrote five songs in a week, which was crazy! And there were other people that did similar amounts.

It was so rewarding to go there and to genuinely get better at writing. I was talking about needing to simplify my writing earlier. Those were notes I got from the masters teachers [at Johnny Mercer]. I'm a wordy writer. I really need people to be sure that I'm getting my point across. And one of the masters teachers, Andrew Lippa, heard one of my songs and said, “I wonder what you're not saying right now.” [That] taught me a lot about writing directly at my problems and trusting that there might not need to be a lot of words [for] people to believe what I'm saying. I [can write that I] am sad and they can believe that or not, but it's not up to me to have to convince them. It's up to me to be honest.

It was an incredible program. Shout out to my small group, where I met Moyana Olivia, who is a fellow Artist in Residence at Keepsake House this year. I met her and Sophie DeLeo in my small group at the Johnny Mercer workshop. And y'all, it's real. The group chat is still blowing up. We get songwriting notes from each other; it is a real community. I'm really happy.

Hailey:

Speaking a little bit about the Artist in Residence application with us, in that application you actually wrote a lot about [...] your experience growing up Arab as well as how important community building is to you. And I'm going to quote you if you don't mind. [You wrote,] "As a member of the SWANA [Southwest Asian and North African] songwriting community, I want to use my music to break down stereotypes about American Arabs and Arabs abroad to ensure that Americans see the humanity inside of the places our country seems to endlessly invade." Can you talk more about this goal? And really this is just a platform for you to talk about this however you want to.

Alex:

As an artist, I like to write about the things [that] keep me up at night. And I only started writing about my Arab identity maybe three, four years ago. Part of that was [because] I'm mixed––[I’m Arab] only on my mom's side, so it's only part of it, and I didn't know how much of that mantle I was allowed to take. But one of the things that I just couldn't stop thinking about––an idea that just kept rattling around my brain is––my grandfather was an Arab man. He was a dark-skinned Arab man who grew up in Boston, and he was a member of the US military and he fought in World War II. And there's this parallel between his service and the service of one of my cousin's fiancé who was killed in Iraq. What my grandfather was doing was a noble cause and was recognized as such, and he came home and he lived a decently long life. He died at 60 of a heart attack. And then I had a soon-to-be member of the family [my cousin’s fiancé] killed for no reason, for a war that we shouldn't have been a part of. They feel disparate at first, but then you start to realize, [this] is the dehumanization of Arab life abroad.

This drew me fucking nuts with the port explosion in Beirut. For the folks [who] don't know, there was this massive port explosion in Beirut [in] August of 2020. It was the biggest story in the news for [about] three days, and then it kind of receded to the background. And with a lot of the commentary around it, there was this implication that it's a normal thing to happen there, it's a normal thing for people in Arab countries to deal with war and explosions, and it isn't! It's something that we have been conditioned to believe. I don't blame Americans for feeling this way, but we get told over and over that it's strategically [smart] for us to give billions of dollars to the Israeli military to commit apartheid, and occupy Palestine. [This] is a part of our psyche.

“We have so much more in common with the people of Iran or the people of Lebanon, who are struggling under US sanctions, or who are not getting the aid that would be designated to other countries with different racial makeups. We have so much more in common with them than we do with the Jeff Bezos’s of the world.”

And I think I have a bit of a responsibility as someone who sees both sides of it. I have been raised in a community that's mostly white; in many ways I'm white passing. But on the other side, that assimilation that my family has been forced into, I'm able to see both sides of it and I want to bring people into the fold. I want to bring people into understanding that we have so much more in common with the people of Iran or the people of Lebanon, who are struggling under US sanctions, or who are not getting the aid that would be designated to other countries with different racial makeups. We have so much more in common with them than we do with the Jeff Bezos's of the world, to bring it back around to one of my favorite punching bags. We have so much more in common with each other, and I want to be able to break down stereotypes about Arab Americans.

[One stereotype is] that we aren't a part of American society, because we are, we are a part of that American fabric. And I am a weirdly proud American, my Postal Service sweatshirt representing. (E.N. not the band---he was wearing an actual USPS shirt.) I'm a proud American, I feel very American in my identity, but I also feel that Arab background as well. And I want to address this head-on with songs like "Blood and Treasure" or "Sit Back," songs of mine where I write directly about the military conflicts that the United States is engaged in, that have taken the lives of my family members. I want to write about that and I also want to be someone who isn't defined by it. Arabs are people who fall in love and live normal lives. I want my writing to be able to contain that and hopefully be a conduit for people so that, the next time these international debates are coming up, [people] really question how much of this is propaganda that we've been fed about what's normal for folks to go through in other parts of the world, versus what we should be stepping back and and questioning as moral.

[...]

We're talking about these chess pieces in geopolitics, but the people there, you know what they're worried about? [They’re wondering,] what am I going to make for dinner tonight? It's like, I don't know, I gotta try something new with my hummus recipe. They are regular, normal human beings trying to live their lives, and we're just disrupting that, and we have so much more in common with them and each other than we do with the people who are at the top making the chess moves.

Autumn:

Thank you so much for talking about that.

So, you are now here with us as an Artist in Residence at Keepsake House. What's that experience been like for you?

Alex:

I've been a resident at Keepsake House for maybe 10 weeks or so. I performed for the first time in December 2022 [at A Keepsake Christmas], and it's been magical. No lie, it's been an unbelievably positive experience.

“Keepsake House really walks the walk when it comes to building community. I have been invited into people’s homes, I have been invited to collaborate on performances and songs, and my experience as a Resident [allows me] to focus on the artistry side of things.”

We've been talking a lot about community, and Keepsake House really walks the walk when it comes to building community. I have been invited into people's homes, I have been invited to collaborate on performances and songs, and my experience as a Resident [allows me] to focus on the artistry side of things. I'm getting to meet all of these incredible residents, both the storytellers and the songwriters who are inspiring me with their work, and entertaining me in all these incredible ways. It's really special. Keepsake is a special place. And I said this at Foresight, but I do not know how Hailey and Jasmine do it. They just draw blood from rocks all day long and create this really special thing for artists, where we get to grow and focus on performing and expand our network with other wonderful artists. It's been amazing.

Autumn:

You are the visionary for the next show that's coming up, Outside the Lines.

Alex:

That is right. Outside the Lines is the next Keepsake show on the calendar. It's happening March 16th. My pitch for this show was on my application, and I'm really excited! It's going to be very chaotic and wacky in a fun way. Me and two other songwriters in the Keepsake family—Morninglory, who was an 2022 Artist from Residence in 2022 famously introduced me at From Story to Song, as well as Ashley Virginia, who is a brand new performer from Greensboro, North Carolina. Ashley and [Morninglory] and I are all going to play a song of our own, and then we each get to cover one of each other's songs as different rounds within the show. And we're not allowed to hear the covers before they happen.

Alex will be performing in the upcoming show, Outside the Lines, at Rockwood Music Hall Stage 3 on Thursday, March 16. Tickets are available now!

Autumn:

So if I'm getting this right, each artist prepares one song from each of the other two artists, they prepare two songs covering the other artists and the original artist doesn't hear the cover until the day of the show. Is that right?

Alex:

Yes, exactly. So I'm going to play one of my songs, one of Livvy's songs, and one of Ashley's songs, and they are not going to know which song or what it sounds like until the day of the show. They're going to live-react. And then we're also working with our [Resident Storyteller] Grace Aki, [who will be improv-interpreting each of these songs as she hears them covered by someone else]. It's gonna be some very crazy chaotic energy and it's gonna be really special. I can feel it already.

I’d had this idea for a show called First Impressions of Each Other, where me and some of my artist friends would cover each other's songs and stuff. Part of the reason I found it to be a cool concept was [that] we all know when you hear a special cover––where they remix it a little bit or they do something different or their voice is a little bit different––you find something new in the song. And it really gets to emphasize different parts of the artistry than when the artist themselves performs the song. And I think it's a really beautiful way of paying tribute to the [parts] that I love in the songwriting of [artists like] Morninglory. Let me emphasize them in my own way, and bring to light new things about these pieces that might not show in the usual performance setting.

Hailey:

We are so excited for this show. It was one of the most Keepsake-esque ideas that we've ever heard.

Last question! At Keepsake House, we talk a lot about the magic in live shows and the communities they help create, almost like every live performance is a keepsake that you cherish from a whole house of life experiences. Tell us about your most memorable or fulfilling live performance, the one you would grab first in a fire.

Alex:

I saw Green Day on the 21st Century Breakdown tour. [That was the first time I saw them live.] I had loved Green Day for years, but I missed them on the American Idiot tour. And I think I was a little too young to go alone, but I went with my best friend. I was 15 or something like that. We were in the general admission pit, and it was this incredible show. Green Day puts on an unbelievable live show––they're leading sing-alongs, they're doing extended bridges or whatever to get the audience hyped. And I moshed for the first time at that show! I crowd surfed for the first time at that show! I truly felt invincible. Like, I'm flirting with danger in all these ways. I'm pushing against people twice my size, and getting vaulted into the air by some bro who thinks it's funny to launch a kid up or whatever. And I was like, this is so dangerous, but I feel so safe, because it feels like there is this community of people around. It's an old stereotype in punk rock circles, like when you get pushed down in the mosh pit, everybody stops, you get picked back up and then you keep going. And that was one of the first times I felt that community and that environment and I felt like, I want to do this. I want to be the person on stage who helps do this for other people.

Follow Alex: