Amplifying Asian Americans: Pseudo Pompous by A.D. Herzel

Pseudo Pompous is the name behind the multi-disciplinary visual art, designs, and writing of Korean American adoptee A.D. Herzel. In this piece, A.D. speaks about the many cultures and identities she navigates, the organic and healing process of creating her art, and her connections to the color gold.

In this monthly blog series, we highlight creative pursuits outside the music industry and by Asian American Pacific Islanders, as part of our mission in amplifying Asian Americans, or #AAA.

Gold is a conflicted color. It is a symbol of reverence, religion, and glamor. In America, gold conjures histories of the gold rush, the race for success, when immigrant workers were used to dig. Gold is the color of class, and is the color most present in the art known as Pseudo Pompous, by the artist A.D. Herzel. “Gold is adoration and corruption at the same time,” said A.D., two sides of a coin that seems to stay with A.D., no matter where she comes from, no matter where she goes.

A.D. was raised in many cultures and places. Adopted from Korea by white Americans alongside two other Korean adopted siblings and three white siblings biological to her parents, A.D. describes her family as “kind of like the fucked up Brady Bunch.” They were Lutheran Long Islanders for a time, then joined a Conservative Sephardic Messianic Cult. A.D. went to private school and only knew a life of religious adherence, until she went to college and was able to understand the nature of her upbringing and separate herself from her parents.

“I didn’t want to paint naked women. I didn’t want to perpetuate that tradition, even though I love painting.”

She studied English in college, but this did not equip her for any specific career. “I graduated in 1990,” said A.D. “It was a pit of a recession and there were no jobs. I could be a waitress or a child care worker or a really bad secretary.” She tried two of those three jobs. After she landed an administrative position at the University of Pennsylvania, she took some painting classes. Even as it became clearer that she had a talent and passion for fine arts, A.D. resisted the traditional path of figure painting. She told us, “I didn’t want to paint naked women. I didn’t want to perpetuate that tradition, even though I love painting.” The decision drove her toward printmaking, and a lack of funds drove her away from a fine arts degree and toward a Master of Education in Art instead.

A.D. and her two sons. Photo by A.D. Herzel.

Juggling art, career, and family has been a constant struggle for A.D. She became a mother at 37 after dealing with years of infertility and then chose to stay home with her two boys for personal reasons. “Being an adoptee and having come to the United States when I was two,” said A.D., “I always knew that I wanted to be at home with my kids, at least until they were two, because I had missed those two years. There’s no memory of my life from zero to two.” The concepts of adoption, reproduction and motherhood have always been interwoven for her. She chose to give her sons what she was never given, but this entailed a greater sacrifice than she had realized.

“You have kids and that [career] trajectory falls off the planet.” A.D. spent 12 years being a full-time mother. She even moved her family to Texas from their long-time home of Philadelphia so that the boys could have access to better schools. They went for education, land, and space, but while her husband put up with toxic co-workers at his new job, A.D. and her sons dealt with the extreme culture shock of moving to a state with few others who looked like them. They would later move to southwest Virginia, and in our interview A.D. recalled, “I don’t know how the hell I raised my sons in the south.”

Her husband’s first job in Texas didn’t last long, so he transferred to an international military contracting position that took him away from his family the majority of the year. A.D. was able to stay home with the kids and her art, but only at the expense of her loneliness. “With him abroad, we’ve had more money than we’ve ever had, but at the same time, he’s not here,” A.D. told us. “I don’t have a husband. My kids don’t have a father. So it’s like a trap, a gilded cage.” Her husband left to provide for them, for the gold sustenance they needed, trapping her inside.

“Art was the one thing that kept me alive, literally,” said A.D. of the first decade of her years at home. “It was my one saving grace.” The meditations came to her first: tiny circles that became patterns and eventually stories, “subconscious unravelings” that came out of her first when her sons were babies, a process that helped her process. Always inspired by nature’s microscopic patterns—fractals, symmetry, tessellations, etc.—A.D. used her own personal vocabulary to create the abstract works that she calls untranslatable. The meditations grew in size and scope through the years, branching into larger pieces about bodily perception and human connection, and spiraling into one of A.D.’s largest parts of her portfolio, the “Gold & Desire” series.

The meditation pieces that started as small spirals were elevated by gold ink and sgraffito in the new series, but they were also created with more intention and form than the first meditations. The gold was attractive, to both the art’s viewers and to A.D. herself, as she continued to navigate various layers of American marginalization: class, race, and gender. And like the cage she felt trapped in while her husband was away working, A.D. described this series as a contradiction, a golden screw of hierarchy and oppression, something both beautiful and terrible. “Gold is like blood for me,” she said.

Blood is a symbol full of contradiction for adoptees. I will admit that, while I was stunned by A.D.’s artwork, I also reached out and asked to interview her for this story because she is an adoptee. Being an adoptee is part of my own identity, learning about adoption a responsibility in my personal education, and meeting other adoptees a connecting and healing experience. When A.D. spoke to her adoptee identity and projects, she made similar admissions and spoke of similar goals.

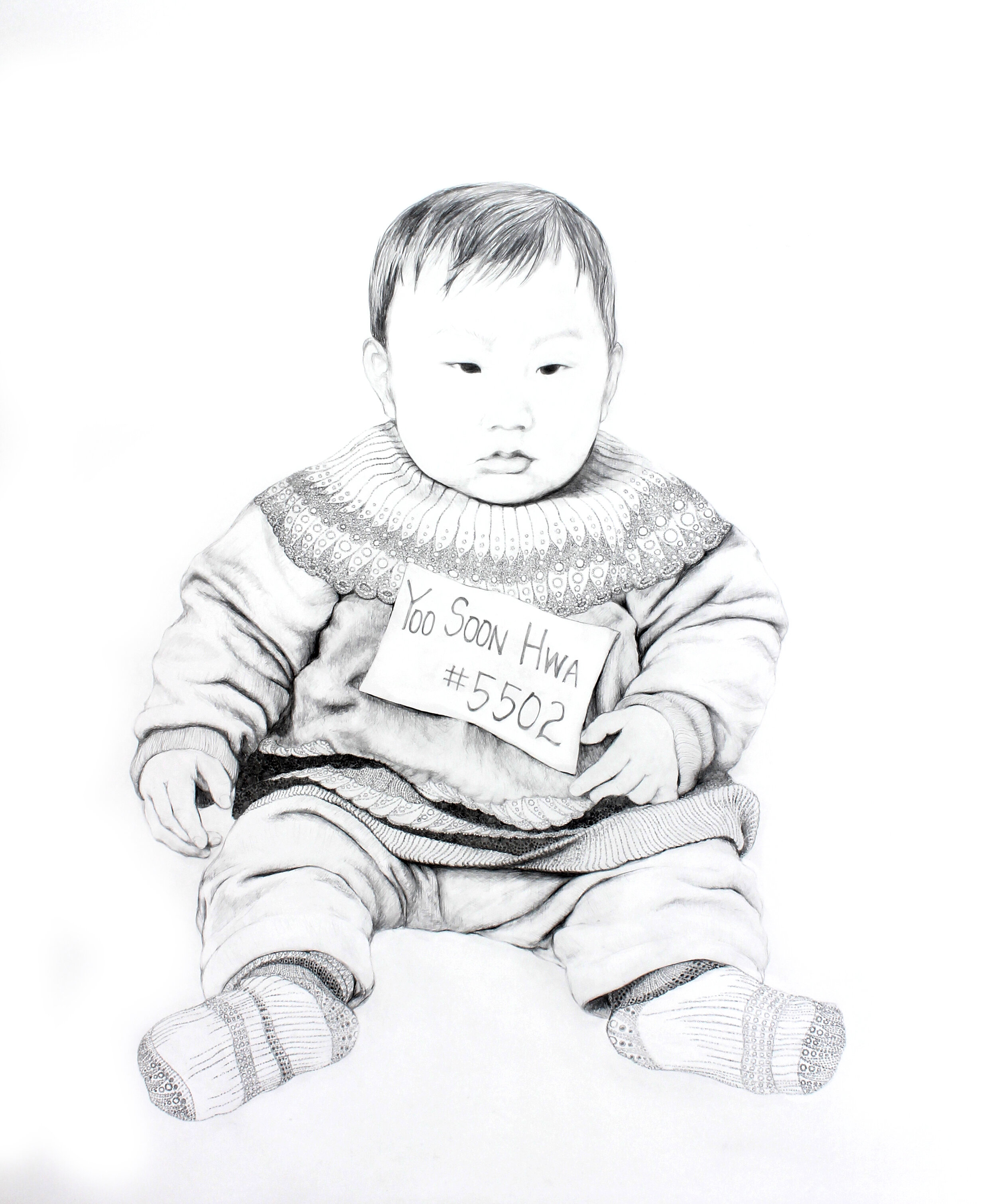

When her adoptive mother passed away, she left A.D. with a folder filled with 50 or so files of orphaned and relinquished Korean children she had sponsored from 1970-1973. Korea, while not the first country to participate in international adoption, was the country where international adoption grew so organized and systematic that it became widely accessible. Korean—and therefore East Asian—babies grew from accessible to desirable in Western countries, and between Korea and China alone, there are hundreds of thousands of transnational adoptees born in Asia who were raised and have reached adulthood in the United States. “Most of us [adoptees] don’t have anything,” A.D. said when speaking about information, from birth parents to birthday to birthplace. From her own file, A.D. learned that she had spent 11 days with her birth parents before being surrendered, a fact she’d never known before and something that is a “really big deal” for adoptees like A.D.

“When I talk to other adoptees I always think, I could be you. This could have been my life. I could have had your family [...] I’m bearing witness to their survival.”

A.D. could not bear to keep the folder for herself. She started posting the photos and other information to adoptee groups on social media, in hopes of finding the people attached to the files. Despite the adoptee community’s interconnectedness, A.D. has not found a match yet. Instead, she has started a portrait series for adoptees. She interviews them, studies and traces and draws and re-draws a photograph until it is memorized, then embeds their likeness into a clay board, often adorned with gold. The portraits are not meant to just tell their subjects’ stories, something adoptees do plenty themselves, but rather are meant to be a process of intimate exchange between the subject and artist. “When I talk to other adoptees I always think, I could be you,” said A.D. “This could have been my life. I could have had your family.” Adoptees are connected in that way: through the unknown, the hypotheticals, the coincidence. The experience of connecting with each other can be, as it has been for me, an act of healing. “I’m bearing witness to their survival,” said A.D., and they are bearing witness to hers.

It is A.D.’s goal to have an adoptee portrait displayed at the Smithsonian, inside the portrait gallery, to make a mark in America’s visual identity. She has learned to reach high and be louder than she was raised to be. “As an artist, you have to make your own parade,” she said, “because nobody else is going to invite you to theirs.” That is ultimately what Pseudo Pompous is: making its own party and making space for A.D.’s voice (and through hers, the many more who see themselves in her work).

A.D. has a number of exhibitions and projects coming up, such as exhibiting the adoptee portfolios in Philadelphia with the Philip Jaison Memorial Foundation. She also has a fundraiser planned for National Adoption Month in November that would pay for the adoptee portraits and allow her to gift them to the adoptees for free. And with every exhibition and project come a loss and, eventually, a rebirth. A.D. told us that all of her pieces feel like shells of herself, and that upon their completion they are like layers she has shed, old skin she has peeled. Perhaps she has never really been digging for gold. A.D. is an artist who leaves gold behind, microscopic and patterned and beautiful shavings of gold.

Follow Pseudo Pompous and support A.D. Herzel’s artwork by purchasing art and prints via her website or joining her Patreon to donate to touring exhibitions: